The Great Plague of Athens

The year is 430 BC. Athens is currently at its “Golden Age” with the great Pericles at the wheel. The democratic state has known an era of splendor and a standard of living higher than any previously experienced. However, the Athenian supremacy in the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean is now highly disputed. Athens has been in a state of war for the second consecutive year with Sparta, a Greek civil conflict that is known in history as “the Peloponnesian War”. We are still at the beginning of a bloody war that will last 27 (!) whole years! The outcome of the war still remains uncertain, but an invisible enemy will alter the balance significantly; a very deadly epidemic, known as the “Great Plague of Athens”.

![Marsyasderivative work: Aeonx <a target='_blank' href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5'>[CC BY-SA]</a> Map during the start of the Peloponnesian War around 431 BC](/images/Blog/Plague%20of%20Athens/Peloponnesian-War-map.jpg)

Thucydides’ narrative

The course of the history of many ancient cultures has been greatly influenced by the emergence of epidemics. Among them, the pestilence that hit Ancient Athens was undoubtedly one of the major contributors to the outcome of the Peloponnesian War, hastening the collapse of Athens’ Golden Age and the Athenian domination in the Mediterranean. It is because of the efforts of one great man and the father of the “scientific history”, the Athenian historian and general Thucydides, that we can shed light today to the events that occurred about 2500 years ago.

“A plague as great as this and with such devastating consequences that it had no similarity in nothing else in human history”.

Thucydides’ work focuses on the History of the Peloponnesian War. His description of the plague that struck Athens in 430 BC follows on from his renowned account of Pericles’ Funeral Oration, the speech that was given by Pericles in Kerameikos cemetery during the public funeral in honor of the war dead. Pericles fell victim to the disease shortly after his speech, however, Thucydides survived it.

![by painter Philipp von Foltz, 1852 [Public Domain] Pericles gives the funeral speech](/images/Blog/Plague%20of%20Athens/Pericles-funeral-oration.jpg)

Athens in crisis

The disease erupted at the beginning of the summer of 430 BC and by the summer of 428 BC it had literally decimated the population of the city. After a brief period of recession, the epidemic broke out again during the winter of 427 BC and lasted until the winter of 426 BC. It is estimated that about one in three residents of Athens was lost in the epidemic, including Pericles, the city's leader. The loss of a large proportion of the human resources and a significant portion of the city’s leaders, coupled with the sharp decline in the morale of its surviving civilians, led to significant errors in the city's political and military choices, which resulted in unconditional defeat and capitulation. After the end of the Peloponnesian War, Athens did not regain in the future even a part of its former power and glory.

The nature of the disease: symptoms and casualties

The reason that caused the Plague of Athens was one of the greatest mysteries of the History of Medicine to this day. The only evidence about the Plague is confined to the narrations of Thucydides, who himself contracted the disease but survived. In his history of the Peloponnesian War, the Athenian historian describes quite precisely the conditions prevailing in Athens during the period of the Plague, as well as the main signs and symptoms of the disease:

"I let everyone, doctor or ignorant, explain, as far as he knows, where he came from and what was the cause of the disease that caused such disorder in the body, leading him from health to death. I, who got sick myself and saw with my own eyes getting sick, will describe the illness and its symptoms so that if it ever happens, everyone will have it in mind and know the illness to get well measures of…”.

The historian mentions North Africa as the likely origins of the disease, which spread in the wider regions of Athens. The disease was very infectious, with high mortality among doctors and relatives who cared for patients. It is estimated that about a quarter or a third of the population of Ancient Athens was lost to the epidemic. Thucydides describes the symptoms in some detail: the burning feeling of sufferers, stomachaches and vomiting, the desire to be totally naked without any linen resting on the body itself, insomnia and restlessness. If the patient survived this first stage, after seven or eight days, the pestilence would descend to the bowels and other parts of the body (genitals, fingers and toes). Some people even went blind. According to Thucydides:

“Words indeed fail one when one tries to give a general picture of this disease; and as for the sufferings of individuals, they seemed almost beyond the capacity of human nature to endure. The most terrible thing was the despair into which people fell when they realized that they had caught the plague; for they would immediately adopt an attitude of utter hopelessness, and by giving in in this way, would lose their powers of resistance. As for offenses against human law, no one expected to live long enough to be brought to trial and punished: instead everyone felt that a far heavier sentence had been passed on him.”

We can see from the recounts of the historian the devastative effects the epidemic had on the Athenian society and the breakdown in traditional values where self-indulgence replaced honor and where there existed no fear of God or man.

![Credit: Everbruin <a target='_blank' href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0'>[CC BY-SA]</a> Thucydides & Herodotus outside Austrian Parliament Building](/images/Blog/Plague%20of%20Athens/Thucydides-on-the-plague-of-Athens.jpg)

Modern theories about the cause of the plague

Based on Thucydides' description, many leading scholars from around the world have at times formulated a series of theories and hypotheses, but have failed to reach safe conclusions as to the cause of the Athens’ Great Plague. The inability to substantiate any hypothesis about the cause of the infection is due to the difficulty of identifying an individual or combination of pathogens as the cause of the epidemic, based on the clinical picture described. Thucydides’ description of the symptoms does not fit into any of the modern forms of infections. Although the credibility and accuracy of Thucydides' references are not disputed, it should be noted that he wrote his famous book some 10 years after the time when the events took place. Indeed, as he did not have specialized medical knowledge, he could have emphasized some of the signs and symptoms of the disease that impressed him most, to the detriment of others, but which may be pathognomonic features for specific diseases. On the other hand, the same disease may not appear the same way today as it did in antiquity. Until recently, about 30 different diseases have been posited as possible causes of the plague, with ebola, malaria and cholera amongst them. However, a recent DNA analysis of dental pulp from teeth recovered from a group tomb in Athens, led by the orthodontist Dr. Manolis Papagrigorakis of the University of Athens, found DNA sequences similar to those of Salmonella enterica, the organism that causes typhoid fever. Nevertheless, the methodology of that study was disputed by other scientists, stating that it led to false conclusions before.

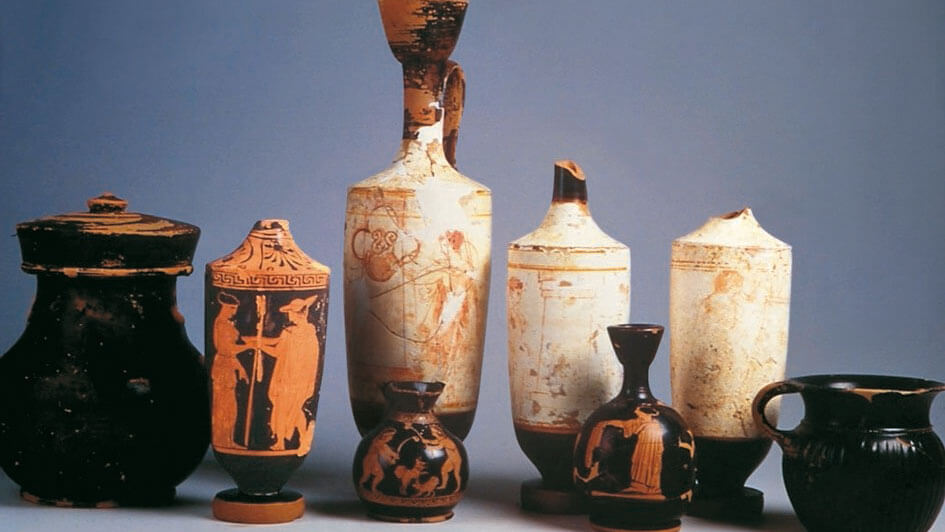

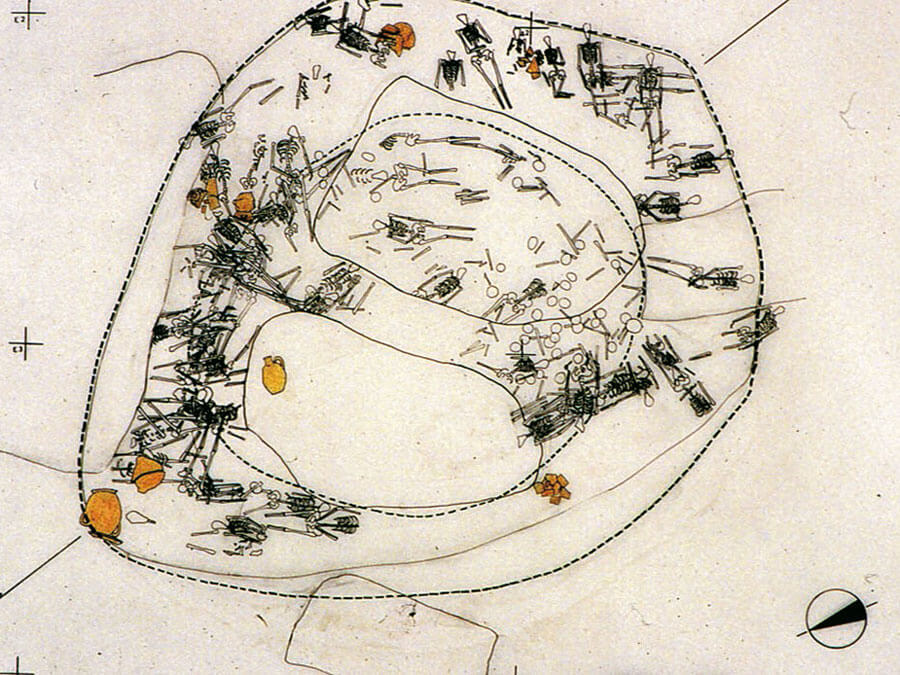

Research on the tomb of Kerameikos

The skeletal material needed to carry out an investigation on the victims of Athens’ Plague was discovered in a relatively recent archaeological excavation of the period 1994-5, which took place in the area of the ancient cemetery of Athens, in Kerameikos. During this excavation, a mass grave of irregular shape was discovered containing about 150 dead, including several children, in the same area where Pericles delivered his famous oration about the war dead and where he was later buried as well, having fallen victim to the disease. This group tomb was dated to the evaluation of archaeological finds between 430-426 BC, that is, in the time of the Great Plague of Athens. According to archaeologists' estimates, the tomb was not of a monumental nature, as the bodies of the dead were found stacked in places suggesting that they were hurriedly buried, without the usual burial customs and respect for the dead. On the basis of these findings, a team of Greek scientists formulated the theory that they were victims of the Great Plague.

Epilogue of an epidemic

The lessons we will learn from today’s pestilence and the coronavirus crisis will come from our own experience of it, not from reading about the Athens Plague. But Thucydides offers us a unique and useful view into a society in war with an invisible enemy and how people face that threat. Quoting Thucydides, “Through knowledge, patience and science we can prevail.” To all out there fighting coronavirus or staying home, humanity has seen countless destructions and survived. Keep strong and keep safe.

![painting by Leo von Klenze (1846) [Public domain] View of "The Acropolis at Athens" in Ancient Athens](/images/Blog/Plague%20of%20Athens/Acropolis-in-Ancient-Athens.jpg)

If you are interested in discovering more about Greek history and culture, you can see more of our blog articles here. Coronavirus is a global crisis, but like others before, it will pass. Nothing is stopping you from making dreams and plans for your next getaway to Greece. If you visit Athens, make sure to join a guided tour in Kerameikos, to delve deeper into the splendor and the humanity of Ancient Athenians. Until then, stay home and stay safe.

*Papagrigorakis MJ, Yapijakis C, Synodinos PN, Baziotopoulou-Valavani E (2006), “DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens”, International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 10 (3), 206-14.

Main photo credit: Michiel Sweerts [Public domain]