The shift from matriarchy to patriarchy in the Greek societies

Over the years, we see a shift from matriarchal to patriarchal societies. If we go as back as the Minoan Crete, circa 2000 BCE, the woman is considered the “spokesperson/daughter” of the great Minoan goddess who defines people’s daily lives. The woman carries the “female power”, continuing the tradition of the prehistoric matriarchal societies. The woman of Crete, as a mother and creator of life, is not inferior to a man. She is seen as a powerful figure who has no reason to fall behind. In Minoan Crete, women had about the same rights and freedoms as men. As the frescoes, seals and other stones with engraved images testify, they took part in every part of social life, like celebrations, competitions, hunting, etc. Like today's women, they combed their hair with care, dyed it, and wore fancy dresses and beautiful ornaments. They even seemed to hold public offices and enjoyed the privilege of high priestesses.

Over the years and with the transition to the Mycenean period, the position of women in society has changed. The Mycenaean civilization, a more war-oriented culture, signifies a shift in power towards the men. Women were not considered lesser but they definitely did not hold the status the Minoan women did.

During the Classical Period, the status of women in society further deteriorated. This was reinforced by the belief that the main social function of the woman is childbirth. The idea was that she finds her own fulfillment in the marriage and that nature has made it so that she prefers the closed and sheltered space of her home that the dangerous and war-ready society of the time.

The role of women in ancient Athens

Women in ancient Athens had no political rights and were considered "minors", while the term "citizen" appeared only at the end of the Classical period. For the Athenian society, women had specific “missions” concerning their homeland; on the one hand, she had to guard the house and perform the duties for its proper functioning; on the other hand, she had to give birth to many children - ideally male - to strengthen the family.

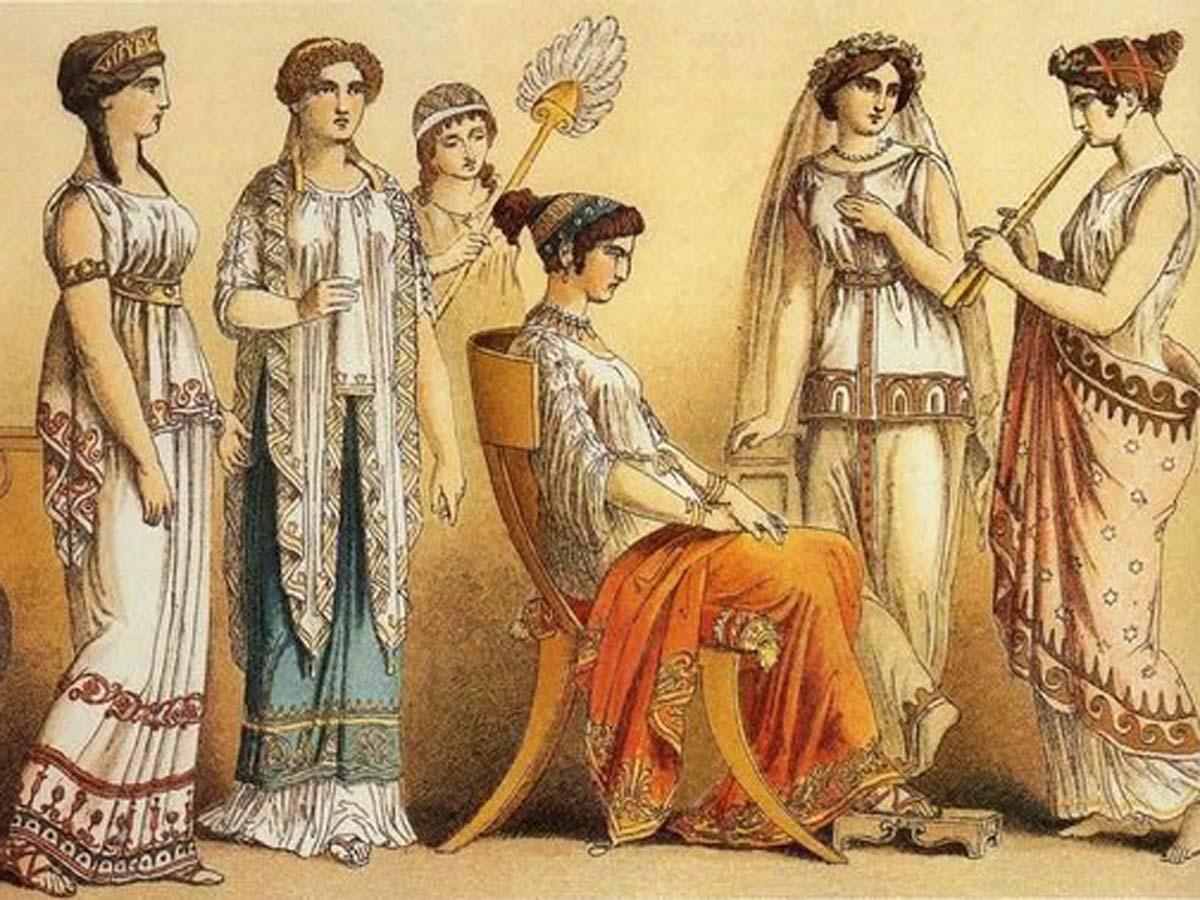

Marriages primarily served social and religious purposes. The girls were married at a very young age to men who were chosen by their fathers. Women spent most of the day at their house, usually on the upper floor of the house (called "gynaeconitis"), knitting or weaving on the loom. These were, after all, the only jobs that were considered to be tailored to women of aristocratic origin.

Their only public outings were large religious festivities, family celebrations, or funerals. There was no institutionalized education for women and any knowledge would come from relatives, girlfriends, or other women in their environment. The mentality of the time is brilliantly portrayed in the famous funeral oration of Pericles, where he states that the ideal for a woman is to do as little as possible for her.

On the contrary, slaves, settler women, and later Athenians enjoyed more freedoms, as they were able to move more freely, such as go shopping and carry water, conduct small-scale trade, or even work as nurses.

There were, of course, also partners, the famous “Hetaires” who were usually slaves or "metoikoi" and played a special role in men's social and erotic life. They kept them company in their symposia, entertained them, and discussed with them various topics, even philosophical ones. They were the only class of women who had a level of education, so as to be able to entertain the men. They were generally more cultured than the other Athenian women; they often knew how to play a musical instrument (lumber or lute), sang and cite poetry. Some Hetaires, such as Pericles' wife, Aspasia, gained fame in Athenian life at the time, indicating that they were not necessarily marginalized. Although monogamy was the norm in ancient Athens, prostitution was not considered illegal, nor were relations with pallakides, the young girls from very poor families who were given to wealthy Athenians by their parents with a purpose no other than to satisfy them sexually whenever they pleased.

These perceptions, naturally, also had an impact on the art of the time. In the Archaic and Classical Periods, female figures in vases and sculptures are generally portrayed in an imaginative way, with no particular emphasis on anatomical features. Exceptions are the depictions of Hetaires, especially in vase painting, who often appear naked, and sometimes take part in erotic scenes. From the second half of the 4th century and especially during the Hellenistic period, the position of women improved significantly and was released from the conservatism of classical times. This change is reflected in the art, with the first appearance of naked female statues (e.g. that of Aphrodite), as well as the manufacturing of female figurines.

The role of women in ancient Sparta

However, the status of women was not exactly the same in all societies of the ancient Greek world. In the oligarchic Sparta, where the abridging of a Spartan warrior was the biggest virtue, free women had more rights and enjoyed greater autonomy than women in any other Greek city-state of the Classical Period. Spartan women could inherit property, own land, make business transactions, and were better educated than women in ancient Greece in general. They did not have to spend their day weaving but rather practicing and shaping their bodies to be strong. During their daily exercise, the Spartan women wore lighter clothes that left their thighs unattended, a fact that the rest of the Greek city-states considered excessive.

The law of Sparta, laid down by Lycurgus in the 9th century BCE, dictated equality among all Spartan citizens and, in contrast to ancient Athens, women were considered proper citizens in ancient Sparta. A bit ironic, considering the fact that Athens is considered the birthplace of Democracy. Girls in Sparta followed the same physical training (albeit not in arms or Greek warfare) and were provided with the same education as men (albeit in their home and not in a public school as the boys). The Spartan women had the freedom to focus on motherhood. Works that were considered menial labor, such as the weaving of clothes, were the responsibility of the helots (slaves). Spartan men were expected to honor the city-state through their participation in the war. Thus, women were the ones running their businesses, farms or estates, managing finances, etc. The purpose of sex within marriage was to create strong, healthy children, but women were allowed to take male lovers to accomplish this same end, something unheard of in the rest of the Greek world.

![Credit: Caeciliusinhorto, <a target='_blank' href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0'>[CC BY-SA 4.0]</a> A Spartan girl running](/images/Blog/Women%20in%20Ancient%20Greece/Spartan-girl-running.jpg)

The role of women after the Classical period in Greece

During the next period, the Hellenistic, women enjoy a form of renaissance regarding their importance as members of society. In the tribal city-states of Thessaly, Epirus and Macedonia, women could even become heads of the state (as long as there was no king). In the region of Thessaly, during the Persian Wars, Thargia became governor of Thessaly and reigned for thirty years. Thessaly's monarchical status allowed her to become queen after her husband, King Antiochus, died. The same seems to have happened in the neighboring kingdom of the Molossians. When the king of the Molosians, Alexander, was absent from Italy, his wife, Cleopatra, took over the position. Her mother was the famous Olympiada, Alexander the Great’s mother. Olympiada was a woman with a fierce personality whose existence alone contributed significantly to the shaping of many historical events of her time. She was taught the priestly secrets at the Dodoni Oracle, which she served for years, while she was also involved in the Bacchus Mysteries and later became a priestess of the Kabbirian Mysteries of Samothrace where she met, fell in love and married Alexander’s father, Philip II.

As we can see from the above, the position of women in ancient Greece largely depended on the place and the period. One very common exam question in Greek schools is this: if you were a woman in the classical period where would you choose to live, in Athens or in Sparta? There is no right or wrong answer, it is a question of critical thinking because of the variety of customs, lands, laws, influences and many more outer and inner criteria in order to understand the role of the woman throughout the ages of Greek antiquity.

Our team has created an inspiring trip to Greece for female travelers, called "Greece for Women: Uncovering the Tales of Goddesses Among Us". Join us and embark on an engaging tour of museums, archaeological spaces and monuments that will shed light on the role of women in ancient Greek society.

You may also find useful:

About the author: Our team at Greek TravelTellers consists of academics and lovers of Greek culture. Our vision is to convey our knowledge and Greek values through unique tours and experiences. Through our blog, we hope to bring Greek history and culture closer to you. Feel free to learn more about us.