Hello, I am Caryatid!

Caryatids were used in gates, facades, cornices, friezes, roofs and so on. The corresponding male architectural figure is called Atlas or Telamon! In ancient architectural art, especially in the Ionic order, the columns were often replaced by a representation of a lustrous female form. In the Doric order, on the other hand, they preferred the men's form. The Caryatids have their hands free while the weight rests simply and lightly on the head, supporting the structure elegantly. Atlas, on the other hand, uses shoulders, back and hands to give the impression of holding a lot of weight. The classic form of Caryatid is dressed in simple but flattering veils and sleeves. She has straight and sloping trunks, and her legs are either both closed or one of them slightly forward. The hands are to the side and down, sometimes holding a tribute in one hand. Foldings on their clothes harmonize with the grooves of the columns, making variations as they follow the curves of the body. The Caryatids were painted in ancient times with many colors, but the colors faded over time.

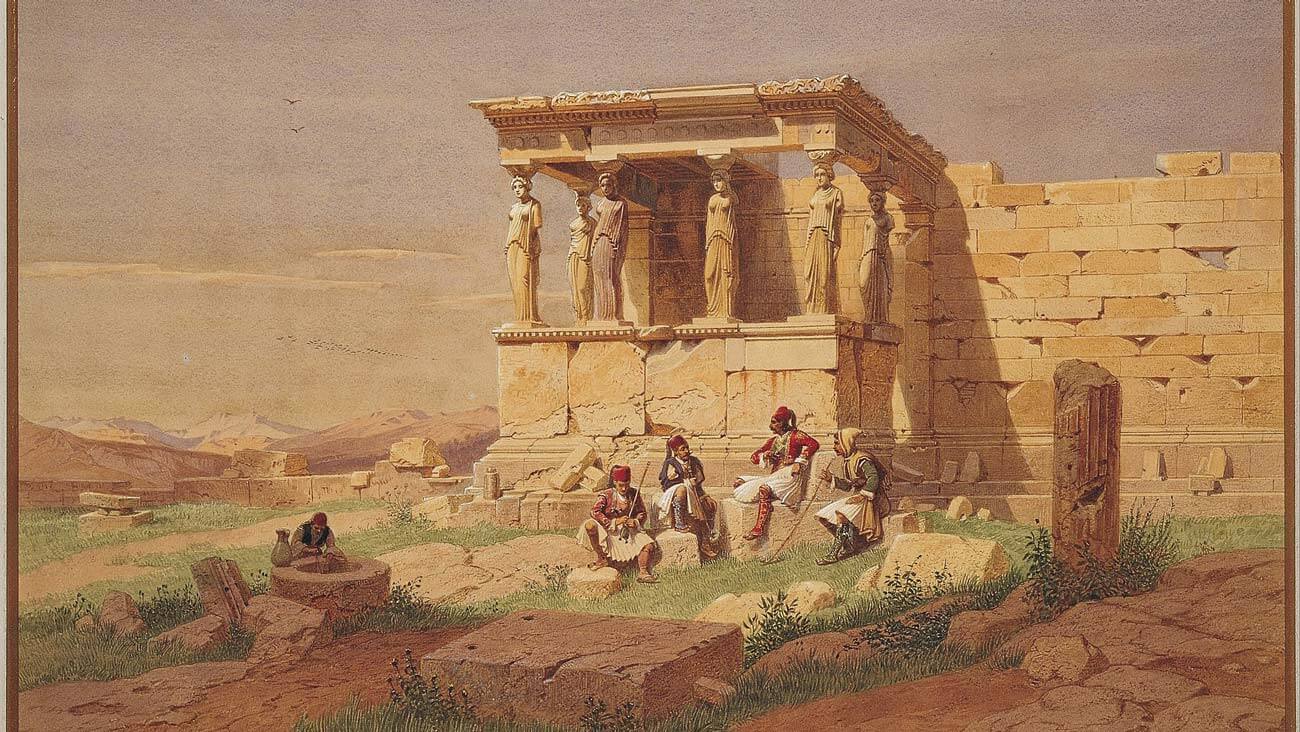

The Caryatids of Acropolis

The most famous Caryatids are the Caryatids of Erechtheion. The six sisters were "born" when their home, Erechtheion, was built on the Acropolis. The Caryatids proudly support the roof, gazing at the Parthenon with an ethereal look. All six of them look very similar, but on closer inspection, one will notice that each one is unique. Their juicy bodies seem to breathe under the folds of the veil, the shoulders are bare, their hair long and tied in a different manner for each elaborate hairstyle. Their legs are bent, they wear a simple Doric veil that forms folds between breasts and rolls effortlessly to the feet. They were painted on the surface, each one a different color which faded on the course of time.

![Credit: Tilemahos Efthimiadis <a target='_blank' href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0'>[CC BY-SA]</a> The Caryatids of Erechtheion](/images/Blog/Caryatids/Caryatids_Maidens_of_Erechtheion.jpg)

The Erechtheion was the most sacred building on the Acropolis. It is a complex marble building, a brilliant example of the Ionic order. The eastern part of the temple was dedicated to the worship of Athena, the patron goddess of the city, while the western part was dedicated to Poseidon-Erechtheus, from which the temple got its name, Hephaestus and other gods and heroes. It is, therefore, a multi-purpose temple, where older and younger cults were housed and where Athens’ most sacred relic, the Palladium (an olive wood effigy of the goddess Pallas Athena) was housed. The building had two extensions. The roof of the northern part rested on six Ionic columns, and beneath its floor, the Athenians showed the sign that Zeus had killed the mythical King Erechtheus. Beneath the throne was the tomb of the other mythical king of Athens, Cecrops.

The southern part though is the best known. Instead of columns, six statues of Maidens supported the roof. The statues are simply called “Korai” (meaning “daughters” or “maidens” in Greek) on a building inscription of the Erechtheion. The name “Caryatids” was given in a later period. One of the Caryatids was removed from the Erechtheion by Lord Elgin in 1801 and is now being held in the British Museum. Efforts by the Greek government to retrieve the Caryatid and unite her with her five sisters in Athens are continuous but have yet to prove successful, with the British government refusing to return her. The Caryatids of Erectheion were replaced by the Greek government with replicas, to protect the originals from the pollution of the city. The original Caryatids are now exhibited in the new Acropolis Museum, with one empty space for the return of their sister from the British Museum.

Caryatids and their origin

These six Korai are now called Caryatids but that was not always the case. There are theories for the origin of their name. According to the theory attributed to Roman writer Vitruvius, the Korai represented the women of Caryae, a small town in Laconia, who was punished for hard labor due to their alliance with the Persians in the second Persian invasion of Greece. These women became the models for the statues of Korai who supported the structure, passing on the burden of their punishment to future generations. This version, which was widely adopted in the Roman period, was later disputed mainly because the Caryatids in their description would have to bear the heavy burden of an eternal punishment when imprinted on marble. Moreover, the Erechtheion’s daughters, with their sweet and proud face, do not respond to this description.

According to another theory, the beautiful, elaborate combed maidens of the Erechtheion owe their name to the virgin priestesses of Artemis Caryatis, a cult of goddess Artemis originated in the small town of Karyai in Laconia. The priestesses, famous for their beauty, would dance in honor of Artemis Caryatis balancing a basket on their head. The obvious question of course and counterargument for this theory is, why would the Korai in a temple associated with goddess Athena be identified with priestesses of goddess Artemis from Caryai.

The creators of the Caryatids is also uncertain. It could have been the sculptor Alkamenis or Kallimachos, or some of Phidias’ students. The exact truth about them was lost over the millennia but their beauty and charm remain unchanged and mesmerizing.

Caryatids: sisters from another mother

The earliest known Caryatids existed in Delphi and date back to the 6th century BC. The Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi was home to the famous Oracle of Apollo and was considered the Omphalos (the Naval) of the Ancient World. City-states, Kings, Emperors and simple men from all over the then-known world would raise monuments and make votive offerings in honor of the god of light and prophecy. The Siphnian Treasury was erected by the city-state Siphnos to win the favor of Apollo and increase the prestige of the donor state. The pediment of the Treasury was supported by two Caryatids, who would later become the inspiration for the Caryatids of Erechtheion on Acropolis. These two Caryatids are on display in the Delphi Museum. One retains much of the trunk and head, with a basket decorated with embossed Dionysian scene with Maenads and Silenus. Their clothes must have been colored (red, blue, green, ocher and gold) making them more vivid and beautiful.

Two other Caryatids, dating in the 1st century BC, decorated and supported the small Propylon of the Sanctuary of Demeter in Eleusis. Huge in size, one is the central exhibit of the Eleusis Archaeological Museum, and the other is at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The "Cistophoric Daughter", as this Caryatid is known, bears in her head a keystone, a cylindrical container that was used for storing food. The Caryatid which is located in the Cambridge museum, carries the same decorative pattern with her sister in Eleusis, while her story is quite similar to the story of the Caryatid of Acropolis grabbed by Lord Elgin. It was taken by Edward Clark, Cambridge doctorate, a specialist in mineralogy, who achieved the transfer of the giant Cistophoric Caryatid from Eleusis to England.

On the 4th of September, 2014, it was announced by the Greek Ministry of Culture that two Caryatids were revealed in the second lobby of the Kasta Tomb in Amphipolis. The two Caryatids are 2.27 meters high, wear a tunic and long fringed heel with rich folds, carry skirts, which are decorated in red and yellow, and their toes are exquisitely detailed. What makes the case of Amphipolis and the Tomb of Kasta special and which has aroused the interest of archaeologists from the beginning, is that the Caryatids in a Macedonian tomb in Greece had never been seen before. According to one version, only those found in the Thracian Tomb of Sveshtari in modern-day Bulgaria, dating back to around 300 BC, can be considered a similar case. The monument was unveiled in 1982, the most notable of which were ten Caryatids, half-humans, half-plants that retained traces of their original coloring, but were unfinished - perhaps an example of the sudden death of the honored dead. The unusual thing is that there is pain and sadness in their faces.

Finally, the "Enchanted" of Thessaloniki, the relief representations that once adorned the two sides of a Corinthian colonnade, have been called the "Caryatids" of the city. Newer than the previous ones (they date in the Roman period, late 2nd century AD), but with a similar history of “abduction” to accompany them, the "Enchanted" are today exhibited at the Louvre Museum. The eight relief figures carried mythological figures related to the worship of Dionysus, such as the god himself, Ariadne, Ganymede, Avra and Dioscorus. Later, the Christians called them "Idols", while the Spanish Jews of the city "Las Incantadas", that is, the Enchanted (or bewitched). They were found near the Ancient Agora, next to Paradise Baths. In 1864, they were removed and transported to France, with the permission of the Ottoman authorities, by French paleontologist Emmanuel Miller. Their story became yet another archaeological documentary entitled "The Enchanted" (2010), a production of the Archaeological Institute of Macedonian and Thracian Studies.

The legacy of the Caryatids

The influence of the Caryatids on architecture and art continued long after their time of creation. We meet them in both neoclassical and modern architecture, as well as in various forms of art - from painting to cinema. Joyful or sad, tormented or proud, sturdy and ethereal at the same time, the Caryatids keep their secrets and continue to captivate us hundreds and thousands of years later. Architects, enchanted by their puzzling mystery, used their form in monumental architectures of the Roman era. Their influence in Roman architecture was such that the first form of the Pantheon of Rome (not the one preserved today), built by Agrippa in 27 BC, had Caryatids on the façade carved by the Athenian sculptor Diogenes.

Caryatids also adorned the attic of the Corinthian colonnades that adjoined the Temple of Mars Ultor at the Forum of Augustus in Rome. These were exact copies, scaled-down, of the Erectheion Caryatids. Hadrian's mansion outside Rome was also adorned with Caryatids, exact copies of the Erechtheion Korai as well. In European architecture, we will find Caryatids in the Baroque and Classical times, e.g. in the Palace of Sanssouci in Germany, as well as later in modern architecture and the art stream of 19th-century historical architecture, e.g. at Hotel Atlantic in Hamburg.

![Credit: Tangopaso [Public domain] Caryatids on the facade of the Renaissance Theatre in Paris](/images/Blog/Caryatids/Caryatids_theatre_Renaissance.jpg)

The maidens were not only famous in the architectural world but also in painting. Jacques-Louis David’s, "The Love of Paris and Helen" (1788) depicts the depth of the scene with Caryatids deeply influenced by the neoclassical movement. The purity of the bodies, the grace of movement and wealth of the Paris and Helen fabrics, which are in the center of the table and form a cluster, give the impression of sculptures. The layout of the interior, the decorative details, and of course the gallery with the Caryatids, reveal the influence of classical antiquity and Caryatids’ impact in the art scene thousands of years later.

![Credit: Livioandronico2013 [Public domain] Caryatids in "The Love of Paris and Helen" by Jacques-Louis David](/images/Blog/Caryatids/Caryatids_Jacques-Louis_David.jpg)

Tall tales and urban myths about Caryatids

Athens, Asomaton street 43: In this little road in Psyri neighborhood there is an imposing neoclassical folk house where two Caryatids support the roof. They are much younger than their "cousins" in the Erechtheion -since this building was built during the 19th century - and they have their arms crossed. The surrounded environment is not related to the classical Acropolis era, but to the popular neighborhood of Psyri. These daughters, however, remain equally beautiful and ardent, holding on to their heads the burden of time.

The urban myth that accompanies their story was created by an imaginative barber who kept his shop on the ground floor for years. Panagiotis Kritikakos used to tell his clients - possibly for the sake of reputation and prominence in the area - that the owner of the building had two daughters who died. Then, the unfortunate father, in order to relieve his pain, ordered that two Caryatids be made for him to remember his korai forever! There were different versions of the stories given by the barber from time to time. Another one wanted the owner's daughters to have been poisoned by their supposedly evil mother, that is, the alleged second owner's wife, who envied and hated them.

The barber’s stories were interesting but far from the real story. This is because the owner's descendants not only denied the story but published photos and other evidence that they all lived happily ever after. The daughters enjoyed their lives and the barber probably left a big beard. The story is charming, but without sudden deaths, as told by Rena Karakatsani, one of the granddaughters of the owner, who was also the sculptor of the Caryatids..!

Admiring the Caryatids today

Today, it is possible to visit and admire the Caryatids in person. When visiting Greece, you should join an Acropolis guided tour, to see the Caryatids of Erechtheion and learn more about the sacred structures of the holy rock of Athena. You will find the original Caryatids inside the Acropolis Museum. You can also take a day trip to Delphi from Athens and visit the Sanctuary of Apollo where you will walk next to the Siphnian Treasury and then admire the Caryatids inside the Archaeological Museum of Delphi! Eleusis is a town nearby Athens and you can visit its archaeological museum where the Cistophoric Daughter is exhibited, while you try to unlock the Eleusinian Mysteries.

You may also like: Women in ancient Greece The role of women in the Classical Period